|

Ernest Wood

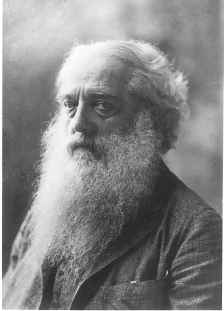

Ernest Egerton Wood was born in England in 1883 and joined the Theosophical Society in 1902. He lectured for the Society for a period of 30 years in 40 countries. He came to Adyar, the international Headquarters of the TS, in 1908 and assisted Annie Besant in educational work, scouting and other areas. He was the founder of the Theosophical College in Madanapalle, which is also the birth place of J. Krishnamurti. He was also the founder and once the Principal of the Sind National College in Hyderabad. He served for several years as secretary to C. W. Leadbeater at Adyar. He married Hilda Wood in 1916. He served as Recording Secretary of the TS from 1929 to 1933, and was a candidate for the Presidency of the Society in the 1934 election. Ernest Egerton Wood was born in England in 1883 and joined the Theosophical Society in 1902. He lectured for the Society for a period of 30 years in 40 countries. He came to Adyar, the international Headquarters of the TS, in 1908 and assisted Annie Besant in educational work, scouting and other areas. He was the founder of the Theosophical College in Madanapalle, which is also the birth place of J. Krishnamurti. He was also the founder and once the Principal of the Sind National College in Hyderabad. He served for several years as secretary to C. W. Leadbeater at Adyar. He married Hilda Wood in 1916. He served as Recording Secretary of the TS from 1929 to 1933, and was a candidate for the Presidency of the Society in the 1934 election.

Prof. Wood was the author of many books, which include A Guide to Theosophy; Reincarnation; Concentration: An Approach to Meditation; Memory Training; Character Building; Destiny; Intuition of the Will; The Seven Rays; Raja Yoga; The Pinnacle of Indian Thought; The Glorious Presence: The Vedanta Philosophy Including Shankara's Ode To The South-Facing Form; Practical Yoga, Ancient And Modern; Seven Schools Of Yoga; An Englishman Defends Mother India; Natural Theosophy, among others. He was awarded the T. Subba Row Medal in 1924 for his contribution to theosophical literature. He also received the title of Sattwikagraganya awarded by the Head of the Mysore monastery in India. He passed away in 1965.

(Source: The Theosophical Year Book 1937)

(From Ernest Wood’s book Is This Theosophy…?)

It is doubtful whether any clairvoyant operates through senses in any way comparable with those familiar to us as sight, hearing and the rest. It is more than probable that when impressions are clearly received in terms of these (as when I heard the sentence relating to the five of clubs) it is due to “visualization” superimposed upon the impression, and forming a species of interpretation. When I put this theory before Mr. Leadbeater he quite agreed to it and wrote a passage to that effect in one of his books.

My own position with regard to Mr. Leadbeater, therefore, was midway between the extremes of acceptance and rejection. It was that of one who had otherwise had convincing proof of the existence of clairvoyant power (though not on anything like the lavish scale presented by Mr. Leadbeater, nor of the perfect accuracy which he always took for granted in his own case), who did not see any reason why Mr. Leadbeater should cheat, but many reasons why he should not do so, who, knowing him and liking him, was prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt where at all reasonable, who at the same time knew that human nature was streaky (like bacon, as it has been said) and did not expect Mr. Leadbeater to be perfect in all respects, even though the devotees thought him to be so.

I found, on the other hand, that most of my friends were rather in the position expressed in an article which I read recently, in which the writer said: “I accept that as true, being ignorant of the matter.” Some few were actually a little afraid of disbelief. They might miss something good, or even “something” might happen to them. I was reminded of the story of the old lady who bowed whenever the devil was mentioned, and when asked why she did so, replied: “Well, minister, it’s best to be ready for everything.”

There had been charges against Mr. Leadbeater of very reprehensible actions with boys, but Mrs. Besant had been satisfied that they were unsound, and had readmitted him to her closest friendship. I am convinced to this day that he loved young people and would do nothing intentionally to harm them, and during the whole of my close contact with him, intermittently covering thirteen years, I never saw in him any signs of sexual excitement or desire. Only once or twice we talked of the attacks made upon him. He said that evidence had been manufactured against him. He had given advice, in good faith, and with the best intentions, which Mrs. Besant had disapproved. In deference to her wishes, he had promised not to give that advice again, although his opinion still was that it was the best under the circumstances. (p. 142-143)

(From The Theosophist, August 1971)

C. W. LEADBEATER

Ernest Wood

[What follows is an appreciation of C. W. Leadbeater by Professor Ernest Wood, which was found amongst Professor Wood’s papers and was sent to N. Sri Ram by Dr. Lawrence J. Bendit.]

Bishop Leadbeater was what I call a great man, by which I mean that the consuming desire of his life was the welfare of humanity, and with him no personal pleasure could be allowed to interfere with that. He was, I am sure, innocent of the sexual passion and interests of which he was accused by persons without sufficient discrimination, but being a man of great courage, independent judgment, unfailing brotherliness and love of personal freedom, in his younger days he dealt with sexual problems of others according to his own knowledge and judgment. He was not a man who had developed any particular talent greatly, because he was essentially responsive to the constant calls of other people, his virtues being essentially those of the best type of country clergyman. He did not, therefore, try and sway large numbers of people, but worked in small groups where this affection could have full effect, and in the belief that the good he could do there would spread. When self-seeking or pushful people tried to intrude into these small circles or impeded his work, he could and did get angry, but this was not deep-seated and he would not deliberately have hurt his worst enemy… His secondary interest was knowledge… In it he showed a definite scientific attitude, by which I mean that he would be very careful about details and would go into his enquiries with an idea of finding facts, not of confirming preconceived ideas. I call this his secondary interest because generally he would delay or set aside this work if there were occasion to attend to young people or his personal groups. I was impressed by his general interest in what he found in the course of his clairvoyant work, and only after some time did I come to think that his personal likes and dislikes might be coloring the results to some extent. My views with regard to this work now, after looking into it in retrospect, are that there were certainly a number of definite errors…

CHARLES WEBSTER LEADBEATER

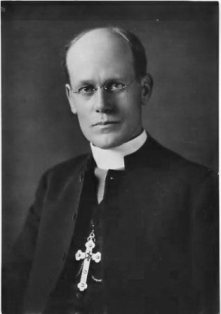

Irving S. Cooper

(Originally published in Theosophy in Australasia, February 1920)

The Rt. Rev. Irving Steiger Cooper was born on 16 March 1882 in California. He was an invaluable field worker for the American Section of the Theosophical Society. He was at one time Honorary Secretary of the National Slum and Prison Improvement League in the USA. He was Regionary Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church in the USA from 1919 and 1935 and established the Church’s Pro-Cathedral in Los Angeles in 1922. His publications include Methods of Psychic Development, Reincarnation: The Hope of the World, The Secret of Happiness, Theosophy Simplified and Ways to Perfect Health. He also wrote the book Ceremonies of the Liberal Catholic Rite. He died in January 1935. The Rt. Rev. Irving Steiger Cooper was born on 16 March 1882 in California. He was an invaluable field worker for the American Section of the Theosophical Society. He was at one time Honorary Secretary of the National Slum and Prison Improvement League in the USA. He was Regionary Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church in the USA from 1919 and 1935 and established the Church’s Pro-Cathedral in Los Angeles in 1922. His publications include Methods of Psychic Development, Reincarnation: The Hope of the World, The Secret of Happiness, Theosophy Simplified and Ways to Perfect Health. He also wrote the book Ceremonies of the Liberal Catholic Rite. He died in January 1935.

I owe more to Charles Webster Leadbeater than to any other man living. My interest in Theosophy dates from a lecture I heard him give in San Francisco in 1903. I knew then that I had found that for which I had been searching, and shortly after I joined the Theosophical Society. His books were the first I studied, and, later, when called upon to lecture, I shamelessly used the information I had absorbed from them. In 1910 I went to India, and there for a space of nearly two years served him as private secretary. Again, after five years of work and lecturing in the United States, I joined him in Sydney in October, 1917, and have been with him ever since.

I have the right to say that I know Bishop Leadbeater as only a few know him. My knowledge of his character and good works is not confined merely to deductions made while listening to his lectures and sermons. I have been with him from early morning to late at night; I have seen him at work and at play; I have prepared his books for publication, and have gone with him on picnics and boating expeditions; I have had access to all his private papers and have read his letters; I have taken many a letter from dictation, and have written many another at his command; in short, I know the details of his daily life and the standards of his ideals.

The least I can say is that never in my busy and varied life have I met a man of nobler character or of finer nature. The very refinement of his speech and the purity of his thoughts were from the first an inspiration to me. Longer association taught me other things. I realized his gentleness, his thoughtfulness of others, the absence of condemnation, even when others did foul wrong. He ever sought to find excuses for those who understood him least. I was amazed at the care with which he conducted his investigations of things unseen, and went back to the study of his books with greater interest than before, realizing for the first time that his least statements were always backed by careful thought. Though he made no outer display, even to those who were with him day after day, I began to appreciate and to value his powers of clairvoyance. About him was none of the clap-trap and humbug usually associated, unfortunately, with the word “clairvoyance.” Rather, he was the trained scientist working in a new field of discovery – new, that is, to the Western world. Yet with all his undoubted power he had not one trace of arrogance, but was always willing to listen to advice or to take suggestions from one much younger and less experienced than he. His love for children and his ever-abiding interest in their welfare was a revelation. Nor was his affection for animals less remarkable. I have seen him spend hours in stimulating affection and mentality in a cat, with the most interesting results. The only time I saw him angry was when a coolie brought in a live cobra, whose back had been broken with a stone. He picked it up and tried to revive it, and only allowed it to be put out of its pain when he saw that nothing else could be done. Above all else, he is a gentleman, with all the fine associations of that fine old word.

But how powerless are words to describe a great character. Silence is oftentimes a finer tribute than a wealth of well-chosen phrases. Bishop Leadbeater often reminds me of a mountain. You recall the words of Marcus Aurelius: “Live like a mountain against which storms dash in vain.” He is like that. He has weathered many storms – that ever seems to be the sad experience of Earth’s greatest children – but they have never affected him. He has quietly worked on with serenity undisturbed. He is so big a man that only on unusual occasions do we realise the noble proportions of his character. His breadth of mind and depth of sympathy are so much a part of him that we have come to take them for granted. He has never sought for recognition, and so is not one of the popularly accepted leaders of the world. The future will value him far more. Already among the few, scattered on five continents, he is known, loved and reverenced. Along the quiet channels of books, lectures, and letters he has poured comfort and knowledge to thousands. We want him to know on this his seventy-third birthday that those he has helped are not ungrateful.

Henry Steel Olcott

(President-Founder of the Theosophical Society)

Adyar, Madras, 17th September, 1905. Adyar, Madras, 17th September, 1905.

C. W. Leadbeater Esq.,

C/o Theosophical Society

42 Margaret St., SYDNEY

My dear Charles,

Accept my best thanks for your excellent article and the covering letter of August 19th. After consultation with the printers I find that we can get in very nicely the diagram and even the green wave-line without too much expense. It will be reduced so as to make it a two-page folding leaf. Of course you have noticed how much I have used of your American lectures in the current and last volumes of the Theosophist. It is because you have the happy talent of conveying very distinctly and succinctly your views: in fact, between your entity and myself and in strict confidence, I may say that the “C.W.L.” personality is about the best writer that we have in the Society, besides being a most fascinating chap. I think it more or less of an outrage that you should give a mere look-in at Adyar of a few days after so prolonged an absence. Although you have not answered my question as to the occupancy of your old octagon room, I am sure that you would prefer it so have arranged to house the officers of the Indian Section elsewhere. I wonder if you would be willing to supply me with a series of chapters from your new book for monthly publication: it might not be a bad idea to get so much of it in type in advance (as I do the O.D.L. [Old Diary Leaves]) thus leaving you no trouble when bringing out the book except to put the chapters in order and send them in to the printer. I should like very much if you would give three of four lectures during the Convention – say afternoons or evenings so as not to interfere with Annie’s morning lectures. If you consent to this please let me know by return of post so that I may make timely announcements. I call your special attention to an article in the October Theosophist entitled “The Awful Karma of Russia”, and will take it as a great favour if you will tell me what can you discover astrally about the lady member in question: she strikes me as being one of the finest characters that I have met. If you can help her on the higher or lower plane, i.e. with spiritual protection, or gifts of money from our colleagues to take her and her children out of that seething social hell please do it.

My dear Charles, you have certainly done splendid work for the movement wherever you have been: I rub my eyes to be sure that it is not a dream and that the fellow who is doing so much is the very same who made me swear so awfully at Adyar and Colombo because of his curate-like limitations. Lord! how I did swear at you – not being the seventh son of a seventh son, hence not a prophet.

I suppose that we shall meet at the Paris Congress in May. Wouldn’t you like to manage it so that we could go together and spend a fortnight or so at the delightful country place with those dear Schuurmans? It would be a jolly rest for both of us. If you can possibly manage it, do leave Australia in time to give me a full week before Convention.

Yours affectionately,

H. S. Olcott

From The Theosophist Supplement, March 1903

List of Mr. Leadbeater’s American Lectures

The following is a list of the subjects of Mr. Leadbeater’s six months course of free lectures now being delivered in Chicago. Some of these have already been published in The Theosophist, and others are to follow.

Man and His Bodies

The Necessity for Reincarnation

Karma – The Law of Cause and Effect

Life After Death – Purgatory

Life After Death – The Heaven World

The Nature of Theosophical Proof

*The Rationale of Telepathy & Mind Cure

Invisible Helpers

Clairvoyance – What it is

do. – In Space

do. – In Time

do. – How it is Developed

Theosophy & Christianity

Ancient and Modern Buddhism

Theosophy and Spiritualism

The Rationale of Apparitions

Dreams

The Rationale of Mesmerism

Magic, White and Black

The Use and Abuse of Psychic Powers

The Ancient Mysteries

Vegetarianism and Occultism

The Birth and Growth of the Soul

How to Build Character

Theosophy in Every-day Life

The Future that Awaits Us

*Reprinted as pamphlet.

From C. W. Leadbeater’s Will

The following is an extract from a letter of C. Jinarajadasa, dated 28 March 1946, to Sri K. S. D. Iyer, Secretary, the Spiritual Healing Centre, R. S. Puram P.O., Coimbatore, South India:

“Bishop Leadbeater left everything to me by his will, including the rights over his books, photographs, etc. This is to state that I cannot give my consent to the use of his photograph in any book which purports to give mediumistic communications from him.”

Bishop Leadbeater’s Sense of Humour

Pedro Oliveira

(Originally published in COMMUNION, Magazine of The Liberal Catholic Church in Australia, Annunciation 2006, vol. 25, no. 1, p.17. Reproduced with permission.)

In spite of his tireless work for the LCC as well for the TS, which involved an astonishing amount of travel, meetings, rehearsals, dictations, etc., Bishop Leadbeater always cultivated a good sense of humour. I will briefly present a few examples of it below.

In a letter to Captain Russell Balfour-Clarke, dated 19th November 1930, and written from Adyar, where he was living at that time, Bishop Leadbeater writes:

“As for myself, I think I may say that I am very fairly well, except for the fact that the axis of my right eye has not yet resumed its normal position. I do not know whether it will ever do so, but I hope that it may, because to see double is distinctly a nuisance, even though it has its humorous side. When one person is approaching me I see two, and I do not know with which to shake hands! When two or three are coming I see quite a crowd, which is a trifling confusing, but one grows used to it; and in descending a flight of stairs it is difficult to know where the edge of the step really is, so I am extra careful to keep hold of the rail! The most interesting experience is to ride in a motor-car, for then I see two roads stretching before me, with quite a considerable angle between them, and of course all the cars approaching on one of them appear to be rushing straight at my car!”

In the same letter he speaks about his cat:

“Pussy is sleeping on the big chair beside me as I write. I have been trying to analyse his excitement when the violin is played , and am much astonished to find that he imagines it is trying to talk to him, and thinks he can understand a word here and there! Then of course it trails off into unintelligibility, which annoys him.”

In The Theosophist, June 1935, we read:

The following item, hitherto unpublished, was written by Bishop Leadbeater from The Manor, Sydney, on May 18, 1932: “There is an item of news in this morning’s paper which so unusual that I think it is worth quoting. It seems that a man living near Daintree was out shooting in the bush one day last week, and fired at a cockatoo. He wounded the poor bird and brought it down to earth, where it lay struggling. He rushed forward and put his riffle butt on the bird to hold it down; the frantic creature’s claws caught in the trigger, the gun went off and shot the man! Unfortunately millions of men have shot birds, but I should think this is probably the first time in history when the bird returned the fire and killed the man. They managed to carry him to the hospital, but he died shortly after admission. What becomes of the bird is not stated. A very curious instance of what Mr. Sinnett used to call ‘Ready-money Karma’, though the jury will have to call it accidental death.”

In February 1934, on his return trip to Sydney from Madras, Bishop Leadbeater had been ill most of the time. The following excerpts of Harold Morton’s report of his last days, published in a circular letter dated 14 March 1934, clearly show that he cultivated his sense of humour to the very end:

“Another little incident of the Tuesday afternoon, two days before he passed over. He had been talking of his forthcoming death with a half-amused expression on his face, when he asked “But does this feel like the grip of a dying man?” And he held out his hand for Heather to clasp and pulled her along. He did the same with me, and we were astonished that he had so much energy left. Right till the very last he used to have most of his meals out of bed, sitting at a table, and less than 24 hours before his expiry I helped the nurse get him in and out of bed.

The afternoon before his passing over, Brother [CWL] spoke for about three-quarters of an hour. As he had not slept much during the previous night, the nurse wanted him to settle down as early as possible. On helping him back to bed, it looked as though he were prepared to doze, so I prepared to leave him. When I got to the door, he sat up in bed, waved his hand in characteristic style, and called out “Well, if I don’t see you again in this body, carry on!” Those were the last words to us, for when we went back to the hospital the following morning, he did not speak to us at all. The nurse asked him if he wished to see his visitors. He opened his eyes and smiled, and I think recognized us; but he did not speak again. He sank then into unconsciousness from which he did not awake.”

Count Hermann Keyserling

(in his book The Travel Diary of a Philosopher)

The reality of many a strange phenomenon which, until recently, was considered impossible, has been proved to-day. Only the ignorant can doubt the truth of telesthesia, of action at a distance, of the existence of materialisations, whatever all that may mean. I was quite certain of this before they had been proved; I knew that they were possible in principle, and considered it out of the question that so many unimaginative people could go through extraordinary experiences which coincide so remarkably, without their being based on some real fact. Anyone who seriously concerns himself with the problem of the interaction of the body and the mind, of the substance and principle of life, will recognise that there is no difference in principle between moving your own hand and moving a distant object. There is also no real difference between affecting your immediate surroundings or some object at a distance. If I can convey thoughts to my neighbour, either by means of words, expressions, a look, or by communicating with him psychically in the technical sense of this term – it is all the same – then this must also be possible in principle in the case of the antipodes, for what is difficult to understand is the power of the mind in influencing matter at all. If this is true anywhere, then the limits of what the mind may effect cannot be discerned, for there are forces which link and permeate all points of the universe. In the same sense, I am quite certain of many things which still await objective proof. In this way I am sure of the existence of levels of reality which correspond with the astral and mental planes of theosophy. Undoubtedly the processes of thought and feeling mean, from a certain point of view, the formation and radiation of forms and vibrations which, although they may not be material in the sense that they escape physical proof, must still be regarded as material phenomena. All appearance is ipso facto material; that is to say, it must be understood in accordance with the categories of matter and force; this applies to an idea no less than to a chemical. For the expression of an idea – whatever be true of its meaning – belongs in all circumstances to the world of phenomena, and it is its expression which gives it substance, which makes it real and capable of being conveyed. In the case of the spoken or written word, this material character of mental formations is obvious; but the same is true in so far as they are only conceived, for even subjective mental images are appearances of something which hitherto did not exist in the visible world, and they are therefore real materialisations of which it has already been proved that they can be conveyed, and posses therefore objective reality. Let us suppose now that it is possible to perceive directly the material formations which are created and pass away in the process of thought and feeling: we would thus have arrived at the higher spheres of occultism. It has not yet been proved scientifically that such a possibility exists in practice. In principle it does exist, and anyone who reads what C. W. Leadbeater, for instance, has told us about these spheres, can hardly doubt that he at any rate does feel at home in them, for all the statements which we can control, in so far as they are directly connected with events in our own sphere of life, are in themselves so probable and agree so perfectly with the known nature of psychic phenomena, that it would be much more remarkable if Leadbeater were wrong. Above all, however, I am inclined to accept as probable the assertion of the occultists for epistemological considerations. There is no doubt that the reality which we experience normally is only a qualified section of the whole realm of reality, whose character is conditioned by our psychophysical organism (this is the real significance of the teaching of Kant: ‘My world is representation’). And this certainty allows us to draw a further conclusion, namely, that, if we should succeed in acquiring a different organisation, then the merely human barriers and forms would lose their validity. Nature, as we perceive her with our senses and our intellects, is only our ‘ Merkwelt,’ as Uexküll would say. The forms of recognition which have been proved by Kant and is followers, relate only to the structural plan of specific souls. If therefore its boundaries can be moved, it should be possible, not only to enlarge, but to exceed the limitations laid down by Kant. Whether this is de facto possible has not yet been ascertained scientifically, but it seems to me to be most significant that the assertions of the occultists correspond from beginning to end with the postulates of criticism: they all teach that the power of increasing experience and experiencing differently is dependent upon the formation of new organs; that the acquisition of powers of clairvoyance is exactly like the acquisition of sight on the part of a blind man, and that the step on to ‘higher’ planes of reality means nothing but stepping beyond the frame of Kantian experience. In any case, all philosophers, psychologists and biologists would do well to concern themselves at long last seriously with occult literature. I have pointed, among the writers who are in question, to Leadbeater, although this clairvoyant does not enjoy general appreciation even among his own group: I did so because I have found his writings, in spite of the frequency of childish traits in them, more instructive than others of their kind. He is the only one whom I know, whose power of observation is more or less on the level of a scientist, and he is the only one whose descriptions are plain and simple. In the ordinary sense of the word he is not talented enough in order to invent what he declares he has seen, nor, like Rudolph Steiner, is he capable of working upon his material in such a way that it would be difficult to differentiate between that which he has perceived and that which he has added. He is hardly intellectually equal to his material. Nevertheless, again and again I meet with assertions on his part, which, on the one hand, are probable, and, on the other, correspond to philosophical truths. What he sees after his own fashion (very often without understanding it) is in the highest degree full of significance. He will, therefore, in all probability have seen something which really exists.

In writing the above I do not in any way wish to defend the system of the theosophists as it exists to-day, nor of any other traditional occult teachings. I have the most serious doubts of the correctness of most of the interpretations which are put upon the observed facts by these systems, and so far as the systems themselves are concerned, I lack every opportunity of testing everything which is not connected with the normal processes of consciousness. I do not know if each plane possesses its own fauna, and I do not know whether there are spirits, elementals or gods, and whether these creatures, if they exist, possess the peculiarities which clairvoyants ascribe to them with tolerable unanimity. It may be; it is certain that nature is much richer than it can possibly appear to our limited consciousness, and an honest man who asserts that he can perceive astral beings is, in all circumstances, more worthy of attentions than all the critics put together who deny the possibility of such experience from empirical or rationalistic considerations. Last but not least – not to leave unmentioned the most extreme possibilities – it is certain that ecstatic visionaries cannot be comprehended exhaustively by the science of medicine. Such men experience what no ‘normal’ being could possible sense, and that their experiences are not merely phantasmagorical is proved conclusively by the fact that ‘godseers’ have always stood on a spiritually higher level than most other men, and history has shown that they have embodied, not only the strongest, but also the most beneficent forces. The most obvious objections against these visions of God was already answered by Al Ghazzali. ‘These are people,’ he wrote, ‘who are born blind or deaf. The former have no idea of light and colour, and it is impossible to teach it to them, and the latter have no idea of sound. In the same way, intellectuals are deprived of the gift of intuitions: does this justify them in denying it? Those who posses it see the design with the eye of the mind. Of course, one could say to them: communicate to us what you see. However, what is the good if I describe to a man possessed of sight a district which he has never seen? No matter how vivid my description may be, he can never acquire a correct idea of it, and a man who was born blind is still less able to do so.’ According to the express evidence of all occultists, a change in the condition of our consciousness is essential before we can experience the supernatural; it appears a priori impossible, therefore, to test occult experiences from our present plane of consciousness. We would be entitled to be radically sceptical if two things could be proved: if, firstly, a change in the condition of our consciousness, which is to open new possibilities of experience, where inconceivable in principle; and, secondly, if the means were not enumerated which would lead to this achievement. Neither supposition is true. The existence of different planes of consciousness, implying different possibilities of experience, is a fact. The observation of a dragon-fly differs from that of a starfish; the world of men is richer than that of the octopus. The differences between the possibilities of experience in differently gifted human beings is scarcely less great. The born metaphysician perceives mental realities instantly, whereas their existence can only be deduced by others, and all metaphysicians experience something of this kind. An intelligent man experiences more and differently than a stupid one; for ‘understanding’ is just as much a direct perceiving of specific realities as ‘seeing,’ and the stupid individual cannot understand. Finally, men, as everybody knows, display abilities in a hypnotic condition which are denied to them in their normal wakened state. In fact, there can be no doubt that there are different conditions of consciousness. As to the path which we must follow in order to reach occult experiences, it has been handed down to us with an exactitude which leaves nothing to be desired. Into the bargain, this tradition has been corroborated unanimously by every sect of occultists. Therefore, the second principal objection is also removed. Anyone who wishes to test the assertions of the occultists should undergo the training which is said to develop the organs of clairvoyance. He alone has a right to controvert the soundness of their dicta who has been trained according to their precepts, and then discovered that he can see nothing. If one of us attempts to dispute their statements, it is equally ridiculous as if he wished to test with the bare eye the soundness of observations which an astronomer makes by the aid of his telescope.

The Indians have done more than anyone else to perfect the method of training which leads to an enlargement and deepening of consciousness. And the leaders of the theosophical movement freely confess that they owe their occult powers to the Indian Yoga. I have discussed these questions in detail with Mrs. Besant as well as with Leadbeater. There is no doubt that both of them are honest, and both assert that they possess possibilities of experience, some of which are known under abnormal conditions, most of which, however, are totally unknown; both of them declare that they have acquired these powers in course of practice. Leadbeater, for instance, originally possessed no ‘psychic’ gifts. As to Annie Besant, there is one thing of which I am certain: this woman controls her being from a centre which, to my knowledge, only very few men have ever attained to. She is gifted, but not by any means to the degree one might suppose from the impression created by her life’s work. Her importance is due to the depth of her being, from which she rules her talents. Anyone who is an adept with an imperfect instrument, achieves more than a clumsy individual does with superior means. Mrs. Besant controls herself – her powers, her thoughts, her feelings, her volition – so perfectly that she seems to be capable of greater achievements than men of greater gifts. She owes this to Yoga. If Yoga is capable of so much, it may be capable of even more, and thus appears entitled to one of the highest places among the paths to self-perfection.

|