|

Contrary to what had been promised by the signatories of the letter to Annie Besant (“utmost secrecy and circumspection”), CWL’s letter to Fullerton was widely circulated among Lodges and members of the American Section. Soon, as details of the scandal became widely known, the Society was thus plunged into a major crisis that would last for two and a half years. As the crisis deepened, Col. Olcott decided to convene an Advisory Board at the Grosvenor Hotel in London, on 16 May 1906, to consider the charges against C. W. Leadbeater. Present at the meeting were Olcott, representatives of the Executive Committee of the American and French Sections; members of the Executive Committee of the British Section, including G. R. S. Mead, Bertram Keightley and A. P. Sinnett. Leadbeater was also present. Mead, Keightley and Burnett, the representative of the American Section, urged that CWL be expelled from the Society. In a letter to Annie Besant, CWL mentioned that “after two hours of discussion and cross-examination, and then an hour and a half of stormy debate at which I was not present, the Committee recommended the Colonel to accept the resignation, which I had previously placed in his hands; he formally did so, and so the matter stands at present.”

A future short biography of CWL, which is in preparation, will present a study of the 1906 crisis, its historical background as well as additional material on the much debated “Cipher Letter” which, it was alleged, was written by Leadbeater to one of the boys at the centre of the events.

After his resignation from the TS, CWL went on to pursue clairvoyant investigations in different parts of Europe which were later to be incorporated in the book Occult Chemistry. He also made investigations on a variety of nature spirits.

A Letter from CWL to Annie Besant

H aving received additional evidence from the American Section of the TS against CWL, Annie Besant issued a circular letter to members of the E.S. on 27th July 1906. It represented a major and dramatic shift in her attitude towards him for she declared that “Mr Leadbeater is so obviously convinced of the propriety of the practice recommended, that he must either be regarded as, on this point, insane, or a victim of that glamour which is the deadliest weapon of the Dark Powers against those who seek to hasten their evolution by treading the dangerous path of occultism. It is this glamour which, I believe, is enwrapping him.” She also wrote: “I have had in Mr Leadbeater a friend, always helpful, always loyal, always kind and considerate, always prompt to sympathize and encourage. My life is the sadder and the poorer for his loss. But the T.S. and E.S. must stand clear from teaching that pollutes and degrades, and it is right that Mr Leadbeater is no longer with us.” aving received additional evidence from the American Section of the TS against CWL, Annie Besant issued a circular letter to members of the E.S. on 27th July 1906. It represented a major and dramatic shift in her attitude towards him for she declared that “Mr Leadbeater is so obviously convinced of the propriety of the practice recommended, that he must either be regarded as, on this point, insane, or a victim of that glamour which is the deadliest weapon of the Dark Powers against those who seek to hasten their evolution by treading the dangerous path of occultism. It is this glamour which, I believe, is enwrapping him.” She also wrote: “I have had in Mr Leadbeater a friend, always helpful, always loyal, always kind and considerate, always prompt to sympathize and encourage. My life is the sadder and the poorer for his loss. But the T.S. and E.S. must stand clear from teaching that pollutes and degrades, and it is right that Mr Leadbeater is no longer with us.”

After receiving a copy of the abovementioned communication, CWL wrote the following letter to Annie Besant. The crisis, however, was far from over and new and unexpected events would take place.

10 East Parade, Harrogate, England

29th August, 1906.

My dear Annie,

Your letter enclosing your circular to the E.S. reached me yesterday while I was writing to you, and my comments upon it were therefore made somewhat hurriedly, as I had to catch a certain post. After a night in which to think it over, it is borne in upon me that I ought perhaps to write a few words more – that if it were thinkable that our positions could be reversed, I should wish to receive from you the very fullest and frankest statement of feeling that was possible. I think I owe it to you and to the loyal friendship of so many years; but I have withheld it so far because I did not wish even to seem to complain or to criticize – because I have to the uttermost that faith in you which you have perhaps somewhat lost in me – also, I think, because I shrank from obtruding my own personality in the midst of a crisis.

As I have said before, when we discussed this matter at Benares, I did not consciously make the slightest mental reservation. I was strongly oppressed by the feeling that the whole affair was taking up much of your time and causing you much trouble, and therefore I proposed as little as possible of alteration in what you wrote to Mrs. Dennis. You may possibly remember that I did make two different suggestions, one concerning that full explanation had never been given by me to Robert Dennis and the other deprecating the emphasis you laid upon the words “in rare cases”. Upon the first you acted, but it gave you the trouble of rewriting a sheet of the letter; the second you did not notice and I did not press it, not in the least realizing then that it might later come to be a question of primary importance. But in explaining matters to you, I did not speak of rare cases, but all where absolute abstention was obviously impossible. You dissented quite definitely from the advice I had given, but there was no slightest hint then about my having “fallen”, or being the victim of glamour.

Now, dear, I am most anxious not to hurt you in any way, and not to give you an impression of a feeling of blame which is utterly absent from my heart if I know it. But from my point of view nothing whatever has happened since, to account for the tremendous change which has come over your opinion. You have received additional evidence from America which is mostly false, which I have never had the opportunity of seeing or of going over with you; and on the strength of that your proclamation was issued. You yourself put my own case for me in the aptest words when you intimated in one of your letters that I might perhaps find it necessary to publish some sort of statement in contradiction to worse rumours that were flying about; you yourself said how monstrous it was that a man’s character should be taken away by unsupported and unexamined evidence given by a few boys who were being so badgered by excited relations that they hardly knew what they were saying. To that has since been added the report (which again I have not seen) of a savagely hostile committee, obviously bent upon making the worst they could of everything; and that is how the matters stand.

I need not remind you of our long work together, of the hundreds of times that we have met out of the body, and even in the presence of our Masters, and of the Lord Himself. We have a record behind us, and you know me well; was I ever an impure person? I have not changed in the least, yet you say now that I have “fallen” from the path of occultism, or rather, I suppose, that I never was really on it at all. Yet recollect how many experiences we shared, and how often it has happened that they were also corroborated by the memory of others. Have you any evidence of this “fall” beyond your own conviction that because I held certain opinions it must be so? If not, will you in justice to me look at the possibilities of the case, and consider whether it is more likely that both you and I and several others should have lived a whole life of glamour for many years (the result of that being, nevertheless, a considerable amount of good work) or that you should now for this once be misinterpreting something?

Pardon me for suggesting that there may be a mistake, but you have yourself allowed it on a far more extensive scale than this. Your theory implies that I have never seen the Masters, and that it has been an evil illusion that has sustained me by its glory and its beauty through the work and the hard struggles of twenty-three years; yet surely that illusion has led me to do work which could scarcely be supposed to be pleasing to any evil powers. My “illusion” of work under the direction of the Masters continues now as ever, and now as ever but the most elevating teaching comes to me from Them, nothing but the most perfect love and compassion. Would you have me deny Them because They have not cast me off? I will say nothing as to the knowledge that They must have had as to the advice I gave, because you would say that They also must be part of my delusion; but you can hardly think me deluded in knowing that Madame Blavatsky trusted me and worked with me though her insight must have shown her my thoughts. (I am not venturing to suggest that They do not perhaps consider that an honest error on such a point makes a man altogether bad.) I am not venturing to suggest that They or she would agree with the advice, I am not venturing to suggest that They do not perhaps consider that an honest error on such a point makes a man altogether bad, or makes it impossible to work with him.

I am not for a moment seeking to convince you that my advice is right; I always recognized that there was much to be said on both sides, and I am quite willing to accept your strong opinion as outweighing many other considerations. But may it not be possible that a man who honestly held an opinion differing from yours may yet not be an impure or abandoned person, that Madame Blavatsky and the Great Ones behind her may have recognized a good an pure intention even in this unconventionalism, and may therefore have thought it possible to use the man in the work? But your message states that you cannot work with me, even though I abandoned that advice in deference to your wishes.

A man holding such opinion cannot remain in the Theosophical Society, but must be cast out of it, even though he change the opinion, apparently! Yet even so, it should not be falsehood that he is cast out, and we have had plenty of it both from our poor dear Fullerton and Mrs. Dennis. Your message contains that inaccurate statement about daily practice and the other about epileptic fits, and (what I felt more than all) the suggestion that I was not quite honest with you at Benares. That perhaps was good for me, for it may be that I was unwittingly a little proud of being always open and honest, so that to be doubted raised for a moment a sort of outraged feeling.

Well, the thing is done now, and with all the weight of you world-wide authority I am branded as a fallen person. Even if upon reflection you do not feel quite so sure that you were right at that moment and wrong during all the previous years, there is no undoing such an action as that. I would not for a moment ask it, because to withdraw would, as it were, stultify you and convict you of acting hastily, which would not be good for your people. Yet if you can modify it in any way, or can contradict for me those things which are definitely untrue, it might perhaps be well – I don’t know. At any rate, I thought I ought to write to you with absolute frankness, so that there should be no possibility of misunderstanding that I could avoid; if I had only been with you, there never would have been any. Ask the Master plainly whether I am abandoned and fallen, and see what is the reply. Believe me when I say that I have never blamed you; I do not wish to get back into the Society, I do not seek to be rehabilitated; but I do want to clear up the position between us if possible. I know very well how hard it is when the mind is once set in a certain groove to drag it out and judge impartially; yet I hope that you may be able to make this stupendous effort, which few in the world could make. But whatever you decide, my affection remains the same.

Yours ever in love and confidence,

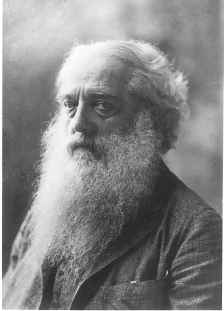

C. W. Leadbeater.

The Mahatmas Visit Col. Olcott

In Col. Olcott’s Diaries, in the entry for 11th January 1907, shortly a month before he died, it is written: “Health not so good. The Mahatmas M. and K.H. visited Col. Olcott and told him he must write C.W.L. and tell him that he made too much haste in deciding the case in London. He said it should not have been made public.” This visit was witnessed by Marie Russak, an American member residing at Adyar, and Rina, Col. Olcott’s nurse. In Col. Olcott’s Diaries, in the entry for 11th January 1907, shortly a month before he died, it is written: “Health not so good. The Mahatmas M. and K.H. visited Col. Olcott and told him he must write C.W.L. and tell him that he made too much haste in deciding the case in London. He said it should not have been made public.” This visit was witnessed by Marie Russak, an American member residing at Adyar, and Rina, Col. Olcott’s nurse.

Olcott’s Diaries show the following entry for the 12th January: “Health better. Col. Olcott feels so comforted that the Mahatmas came, and says it seems like the old days in New York when they came so often through H.P.B.” The entry for the 13th January says: “The Blessed Ones came again and heard the letter to C.W.L. and the article. They approve, and Mahatma M. dictated some of the article. He begged us to expedite matters.”

When Col. Olcott’s article was finally published in The Theosophist (February 1907), there was skepticism and opposition among members in England and America to what was called the ‘Adyar manifestations’. There was even a suggestion that they had been engineered by Leadbeater himself, who was then in Taormina, Italy! But Olcott had recorded in his Old Diary Leaves actual visits from the two Mahatmas: Mahatma M. visited him in New York in 1877 and left him his turban, and Mahatma K.H. visited him outside Lahore in 1883.

We reproduce below portions of Col. Olcott’s article (“Recent Conversation with the Mahatmas”). In it he makes reference to the polarization which was affecting the Theosophical Society at that time:

“The principal members of the two parties were rather startled recently by the statement of Mrs. Annie Besant (made privately, but not generally known) that she thought that she must have been under a glamour, in supposing that she had worked with Mr. Leadbeater, while he was giving such harmful teachings, – under the guidance, and in the presence of, the Mahatmas. I wished to make my own mind easy about the matter, so I asked the Mahatmas this question: “Is it then true that Mrs. Besant and Mr. Leadbeater did work together on the Higher Planes, under your guidance and instruction?” Answer. (Mahatma M.) “Most emphatically yes!” Question. “Was she right in thinking that because Mr. Leadbeater had been giving out certain teachings that were objectionable, he was not fit to be your instrument, or to be in your presence?” Answer. “No. Where can you find us perfect instruments at this stage of Evolution? Shall we withhold knowledge that would benefit humanity, simply because we have no perfect instruments to convey it to the world?” Question. “Then it is not true that they were either of them mistaken or under a glamour?” Answer. “Decidedly not. I wish you to state this publicly. (…)

The Mahatmas wished me to state in reference to the disturbances that have arisen because we deemed it wise to accept Mr. Leadbeater’s resignation from the Society, that it was right to call an Advisory Council to discuss the matter; it was right to judge the teachings to which we objected as wrong, and it was right to accept his resignation; but it was not right that the matter should have been made so public, for we should have done everything possible to prevent it becoming so, for his sake as well as for that of the Society.”

Col. Olcott passed away on 17th February 1907, and Annie Besant, having been nominated by him as his successor, was elected President of the Theosophical Society in May of that year. The Mahatmas’ visit to Olcott caused her to change her view regarding CWL but more events would still unfold in this which was one of the major crisis in the history of the Society.

CWL is reinstated in the TS

A s the crisis persisted, mainly in America and in England, Annie Besant wrote a Letter to the Members of the Theosophical Society in November 1908 as a result of an appeal made to the General Council and to her “to take action to put an end to the painful condition of affairs which has arisen in consequence of certain “pernicious teaching” ascribed to Mr. C. W. Leadbeater.” In her letter, referring to the Advisory Board meeting convened in London, May 1906, which considered the charges against C. W. Leadbeater, she said: s the crisis persisted, mainly in America and in England, Annie Besant wrote a Letter to the Members of the Theosophical Society in November 1908 as a result of an appeal made to the General Council and to her “to take action to put an end to the painful condition of affairs which has arisen in consequence of certain “pernicious teaching” ascribed to Mr. C. W. Leadbeater.” In her letter, referring to the Advisory Board meeting convened in London, May 1906, which considered the charges against C. W. Leadbeater, she said:

“The so-called trial of Mr. Leadbeater was a travesty of justice. He came before judges, one of whom had declared beforehand that “he ought to be shot”; another, before hearing him, had written passionate denunciations of him; a third and fourth had accepted, on purely psychic testimony, unsupported by any evidence, the view that he was grossly immoral and a danger to the Society; in the commonest justice, these persons ought not to have been allowed to sit in judgment. As to the “evidence”, he stated at the time: “I have only just now seen anything at all of the documents, except the first letter”; on his hasty perusal of them, he stated that some of the points “are untrue, and others so distorted that they do not represent the facts”; yet it was on these points, unsifted and unproven, declared by him to be untrue and distorted, that he was condemned, and has since been attacked.”

She also commented on the “Cipher Letter” allegedly written by CWL to one of the boys in his care:

“Much has been made of a “cipher letter.” The use of cipher arose from an old story in the Theosophist, repeated by Mr. Leadbeater to a few lads; they, as boys will, took up the cipher with enthusiasm, and it was subsequently sometimes used in correspondence with the boys who had been present when the story was told. In a typewritten note on a fragment of paper, undated and unsigned, relating to an astral experience, a few words in cipher occur on the incriminated advice. Then follows a sentence, unconnected with the context, on which a foul construction has been placed. That the boy did not so read it is proved by a letter of his to Mr. Leadbeater – not sent, but shown to me by his mother – in which he expresses his puzzlement as to what it meant, as he well might. There is something very suspicious about the use of this letter. It was carefully kept away from Mr. Leadbeater, though widely circulated against the wish of the father and the mother, and when a copy was lately sent to him by a friend, he did not recognize it in its present form, and stated emphatically that he had never used the phrase with regard to any sexual act. It may go with the Coulomb and Pigott letters.”

(Emma and Alexis Coulomb were workers at the headquarters of the TS at Adyar who participated in a conspiracy with Christian missionaries in Madras against Madame Blavatsky in 1884. Richard Pigott was a journalist for The Times in London in the 1880s, well known for the 'Pigott forgeries' against Charles Stewart Parnell.)

Towards the end of her letter Annie Besant wrote:

“If the Theosophical Society wishes to undo the wrong done to him, it is for the Convention of each Section to ask me to invite his return, and I will rejoice to do so. Further, in every way that I can, outside official membership, I will welcome his co-operation, show him honor, and stand beside him. If the Theosophical Society disapprove of this, and if a two-thirds majority of members of the whole Theosophical Society demand my resignation because of this, I will ask my Master’s permission to resign. If not, is it not the time to cease from warring against chimeras, and to devote ourselves wholly to the work? The trouble is confined to a small number of American and a considerable number of British members; can they not feel that they have done their duty by two years and a half of protest, and not endeavor to coerce the remainder of the Society into a continued turmoil?”

At its meeting in December 1908 at Adyar, the General Council – the Theosophical Society’s governing body – approved by a vote of 23 out of 25, of which 13 were votes of the 14 Sections (see A Short History of the Theosophical Society compiled by Josephine Ransom), the:

Inviolable liberty of thought of every member of The Theosophical Society in all matters philosophical, religious and ethical, and his right to follow his own conscience in all such matters, without thereby imperilling his status within The Society, or in any way implicating in his opinion any member of The Society who does not assert his agreement therewith. That in pursuance of this affirmation of the individual responsibility for his own opinions, it declares there is no reason why Mr. C. W. Leadbeater should not return, if he wishes, to his place in The Society which he has in the past served so well.

Ransom recorded in her abovementioned book: “The voting for the reinstatement of Mr. Leadbeater was 21 out of 24. He accepted the invitation to return.” There were strong protests in the English Section of the TS regarding the proposal to reinstate CWL and when the Section’s Convention, held in November 1908, decided by a narrow majority in favour of the proposal, more than five hundred members resigned from the Society as a result. CWL arrived at Adyar on 10 February 1909, accompanied by the Dutch scholar Johan van Manen.

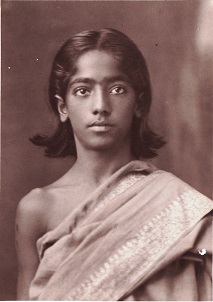

The Discovery of Krishnamurti

At Adyar CWL took up residence in the Octagonal Bungalow, also known as the River Bungalow, where he had lived in 1885. His return to Adyar after two and half years of turmoil would represent another milestone in his life and in the life of the TS. Although working strenuously from very early hours dictating letters and articles, it was his habit at around five o’clock every evening to go to the Adyar beach for a swim. One day in the second half of April 1909, while walking back from the beach with his assistant Ernest Wood, CWL told him that one of the boys he had seen on the beach had “the most wonderful aura he had ever seen, without a particle of selfishness in it”. He predicted that the boy one day “would become a spiritual teacher and a great orator.” “As great as Mrs Besant?” asked Wood. “Much greater” replied CWL. For those who knew his profound respect and admiration for Annie Besant the above statement was nothing short of extraordinary. (Source: Krishnamurti –The Years of Awakening by Mary Lutyens, London: John Murray, 1975). At Adyar CWL took up residence in the Octagonal Bungalow, also known as the River Bungalow, where he had lived in 1885. His return to Adyar after two and half years of turmoil would represent another milestone in his life and in the life of the TS. Although working strenuously from very early hours dictating letters and articles, it was his habit at around five o’clock every evening to go to the Adyar beach for a swim. One day in the second half of April 1909, while walking back from the beach with his assistant Ernest Wood, CWL told him that one of the boys he had seen on the beach had “the most wonderful aura he had ever seen, without a particle of selfishness in it”. He predicted that the boy one day “would become a spiritual teacher and a great orator.” “As great as Mrs Besant?” asked Wood. “Much greater” replied CWL. For those who knew his profound respect and admiration for Annie Besant the above statement was nothing short of extraordinary. (Source: Krishnamurti –The Years of Awakening by Mary Lutyens, London: John Murray, 1975).

In a question and answer session with TS members in Washington, D.C., during his lecture tour of the United States in 1922-23, which was included in the booklet Clairvoyant Investigations by C. W. Leadbeater and “The Lives of Alcyone” (J. Krishnamurti) – Some Facts Described by Ernest Wood with Notes by C. Jinarajadasa (1947), Ernest Wood reminisced about Krishnamurti and his interaction with CWL:

I was there when Krishnamurti appeared with his father at Adyar and I knew him before Mr. Leadbeater did. He was a school boy. When we first knew Krishnamurti he was a very frail little boy, extremely weak, all his bones sticking out, and his father said more than once that he thought probably he would die, and he was having a bad time at school because he did not pay any attention to what his teachers said. He was bullied and beaten to such an extent that it seemed the boy might fade away from this life and die, and the father came to Leadbeater and said: "What shall we do?" Mr. Leadbeater said, "Take him from school and I will inform Mrs. Besant." Mrs. Besant had done much for Hindu boys. She had the Central Indian College, in which many of the boys were entirely maintained by her – food, shelter, education, everything. So it was nothing unusual for her to look after boys. Mrs. Besant was in America at the time. She replied that she would be very pleased to see to their welfare, so the two boys were taken from the school; Krishnamurti's younger brother was all right, but they didn't want to be separated; and some of us agreed to teach them a little each day so that they might be prepared to go to England for their further education. Seven or eight of us taught them a little each day. The boys used to sit in Mr. Leadbeater's or one of the adjacent rooms, with their teacher. I do not know that it could be said that Leadbeater trained him in any sort of particular way. To be anywhere near Mr. Leadbeater was a training for anybody. He made him drink milk and eat fruits. Krishnamurti did not like this. He [C.W.L.] attended to his health. He did not much like this eating fruits and milk, but did it. He also arranged for swimming and exercises in the way of cycling and other things, and they played tennis in the evening, so that very soon Krishnamurti was quite a healthy and strong boy and began to take more interest in the world. I think that he must have been always more or less psychic and therefore did not pay attention to his teacher. I noticed very soon that Krishnamurti used to collect people's thoughts, and I have seen him do some quite remarkable feats of conversation with dead people while still a little boy, and that developed quite naturally. I do not know of any special and deliberate training in that way. In Mr. Leadbeater's room and in his company, of course, he really received the best of training in courtesy, etc.

Thus began another eventful period in the life of both CWL and theTheosophical Society in which Krishnamurti would play a major role.

|